Obesity in Children & Teens

Obesity is one of the most common chronic diseases of childhood. In 1998, the National Institutes of Health defined it as a chronic disease. This designation was an attempt to destigmatize obesity and recognize its causes, which include genetic, environmental, psychological, and socioeconomic factors. Since the environment is obesogenic, and obesity is a risk factor for significant comorbidity, it is essential to diagnose and treat obesity in a non-stigmatizing and evidence-based manner.

Key Points

Multifactorial considerations

Obesity is multifactorial and not a result of personal or familial

failure. Racism, poverty, and other social determinants of health are important

risk factors to consider.

Diagnosing obesity

Body mass index (BMI) is the most straight-forward and commonly

available tool for diagnosis of obesity.

Screen for comorbidities

Obesity is both a chronic disease as well as a risk- factor for

other chronic diseases. The more severe the obesity, the higher the risk for

comorbidities. [Skinner: 2015] Screening for

comorbidities is a cornerstone of obesity management (see below for screening

guidelines).

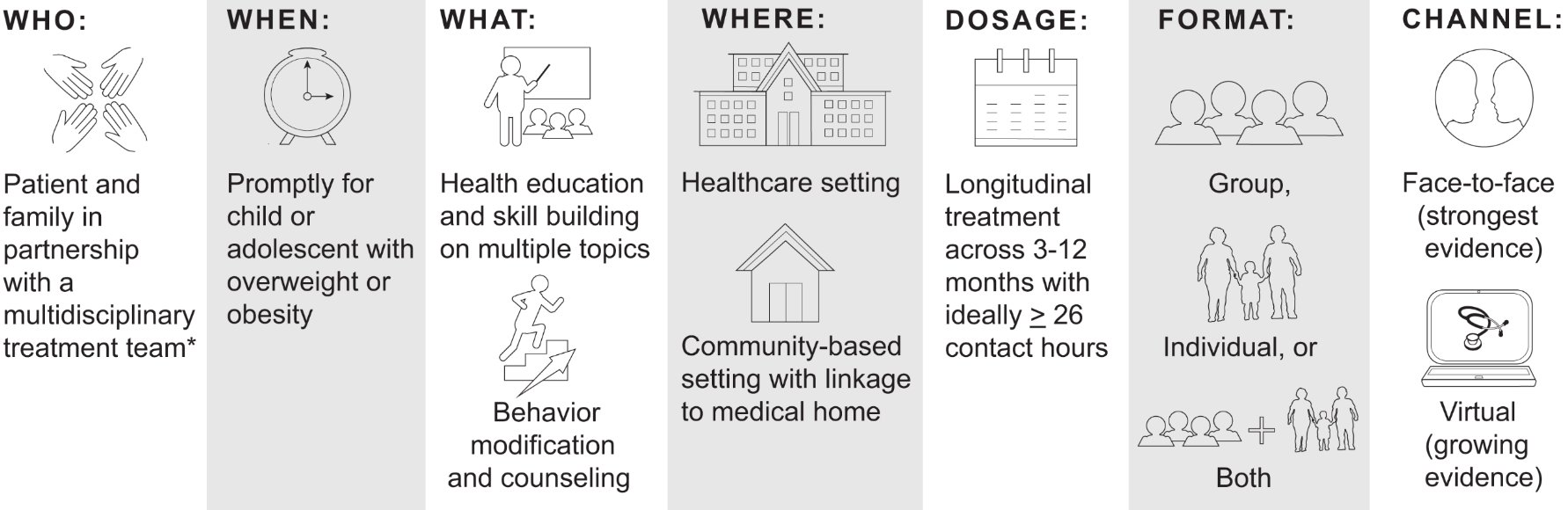

Management

Treatment includes nutrition support, physical activity treatment,

behavioral therapy, bariatric surgery, and pharmacotherapy. There is no evidence

to support watchful waiting.

Weighing treatment risks

Risks of treatment include weight fluctuations and disordered

eating. Multiple studies have shown a decrease in disordered eating when

children are enrolled in structured weight management programs. Current

guidelines stress that the risks of obesity and comorbid conditions outweigh the

risks of treatment.

Role of primary care

The medical home is pivotal in diagnosing, treating, and

preventing childhood obesity. [Daniels: 2015]

Primary prevention includes efforts to influence, in healthy directions, the

eating and activity behavior of all children. Secondary prevention efforts are

those thrisk at are directed toward children who, for whatever reason, are at

greater than average risk of becoming obese. Tertiary prevention is designed to

prevent the consequences of obesity and would be considered treatment. Treatment

details can be found below. [Daniels: 2015]

Practice Guidelines

In 2023, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) released a new Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Treatment of Children with Obesity. The full report and executive summary are listed below:

-

Hampl SE, Hassink SG, Skinner AC, Armstrong SC, Barlow SE, Bolling CF, Avila Edwards KC, Eneli I, Hamre R, Joseph MM, Lunsford D, Mendonca E, Michalsky MP, Mirza N, Ochoa ER, Sharifi M, Staiano AE, Weedn AE, Flinn SK, Lindros J, Okechukwu K.

Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Obesity.

Pediatrics. 2023;151(2). PubMed abstract / Full Text -

Hampl SE, Hassink SG, Skinner AC, Armstrong SC, Barlow SE, Bolling CF, Avila Edwards KC, Eneli I, Hamre R, Joseph MM, Lunsford D, Mendonca E, Michalsky MP, Mirza N, Ochoa ER, Sharifi M, Staiano AE, Weedn AE, Flinn SK, Lindros J, Okechukwu K.

Executive Summary: Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Obesity.

Pediatrics. 2023;151(2). PubMed abstract / Full Text

Screening for Risk Factors

Screening children for risk factors associated with obesity is the principal method for determining which children are candidates for secondary prevention efforts. Screening involves assessing factors from the history and observing an infant or child’s growth pattern. In the 2023 guideline, the American Academy of Pediatrics places increased focus on how social determinants of health and systemic factors increase risks for individuals. The presence of risk factors should prompt the provider to provide early anticipatory guidance for overweight and obesity prevention.

The AAP consensus recommendation is to “perform initial and longitudinal assessment of individual, structural, and contextual risk factors to provide individualized and tailored treatment of the child or adolescent with overweight or obesity." [Hampl: 2023]

Risk Factors

Studies have consistently shown that overweight and obesity are influenced by genetics. However, the degree to which individuals are affected varies. A 2012 meta-analysis with 115 studies found that BMI heritability ranged from 47-90% and 24-81% in twin and family studies, respectively. [Elks: 2012] Parental obesity more than doubles the risk of adult obesity among children under 10 years of age. [Whitaker: 1997] Furthermore, it is important to note that it is not just genetics that affects risk. Genetic, environmental, and behavioral factors modulate this risk and result in intergenerational transmission of adiposity. [Hampl: 2023]

Epigenetic and Prenatal Factors

Although mechanisms are

poorly understood, the intra-uterine environment in which an infant develops

can alter the way genes are expressed.

- Maternal BMI and gestational weight gain are both associated with increased rates of childhood overweight and obesity. [Larqué: 2019]

- Infants and children born to mothers with gestational diabetes have greater adiposity at birth and risk of overweight and obesity in childhood. [Logan: 2017]

- Both environmental tobacco smoke and maternal smoking during pregnancy are associated with increased risk of overweight and obesity. [Qureshi: 2018]

Low (<2500 g) and high (>4000 g) birthweight are associated with higher risks of overweight and obesity. [Larqué: 2019]

Evidence is inconclusive; however, some studies have suggested that early breastfeeding cessation is associated with childhood overweight and obesity. [Larqué: 2019]

Children with rapid early weight gain, defined as crossing 1 or more percentile lines on growth charts in their first two years of life are up to 3.6 times more likely to have overweight and obesity as children and adults. [Zheng: 2018]

The environment in which a child grows has the potential to negatively or positively affect the risk of developing overweight or obesity. For example, studies have shown that children of lower socioeconomic status (SES) are at higher risk of developing obesity. [Hales: 2017] This association is multifactorial and is impacted by public policy factors, how unhealthy food is marketed, school environment, education, access to fresh food or food insecurity, and access to safe physical activity. [Hampl: 2023]

CYSHCN are 27% to 59% more at risk than typically developing children to become overweight or obese. [Bandini: 2015] For example, CYSHCN may have less healthy dietary and physical activity patterns because of medical conditions (e.g., spina bifida or cerebral palsy) that limit or restrict opportunities to be physically active. [Minihan: 2011] They may be taking medications such as atypical antipsychotics (e.g., risperidone), antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and anticonvulsants that increase their risk of excess weight gain. [Vanina: 2002] It is important to carefully monitor the growth patterns of CYSHCN to recognize which of them may be showing a trajectory that may lead to obesity.

Screening for Obesity

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that pediatricians and other primary health care providers annually screen all children ages 2-18 years old for overweight (BMI ≥ 85th percentile to <95th percentile), obesity (BMI ≥ 95th percentile), and severe obesity (BMI ≥ 120% of the 95th percentile for age and sex) using age- and sex-specific CDC growth charts. Furthermore, due to its ease of use, reproducibility, and sensitivity/specificity, the AAP recommends using body mass index (BMI) as the primary screening and diagnostic tool. [Hampl: 2023]

Body Mass Index (BMI)

62 KB)

BMI Females 2-20 Years (CDC) (

62 KB)

BMI Females 2-20 Years (CDC) ( 68 KB)), websites

(BMI Percentile Calculator for Children and Teens (CDC)), and apps are available to assist with calculating the

BMI and assessing the percentile.

68 KB)), websites

(BMI Percentile Calculator for Children and Teens (CDC)), and apps are available to assist with calculating the

BMI and assessing the percentile.

Screening for Comorbidities

Children and adolescents with overweight and obesity are at increased risk of associated comorbidities, such as hypertension (HTN), dyslipidemia, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), depression, abnormal glucose metabolism and diabetes, slipped capital femoral epiphysis, and polycystic ovarian disease. Although the risk of certain comorbidities is greater among certain racial and ethnic groups, it is important to note that the etiology is multifactorial and is related to the impact of genetic, environmental, and social factors. [Divers: 2020] Screening for these comorbidities should form part of the evaluation of the overweight and obese child, given that weight loss interventions can improve many of these conditions. [Rajjo: 2017] As with any other condition, this begins by obtaining a thorough history, which should include the patient’s trends regarding diet, lifestyle, activity, a family and social history that focuses on obesity-related comorbidities and risk factors, and medications that increase obesity risk.

The review of systems and physical exam should be used to assess for comorbidities. For example, a patient with obesity reporting polyuria coupled with acanthosis nigricans found on exam may have diabetes. The AAP Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Treatment of Children and Adolescents provides comprehensive tables with common system complaints and physical exam findings along with their associated obesity-related causes.

Evaluation

The prevalence of abnormal lipids is 3x higher in children with obesity compared to those with a healthy BMI. [Nguyen: 2015] The AAP recommends screening for dyslipidemia with a fasting lipid profile in children 10 years and older with obesity (BMI ≥ 95th percentile) and overweight (BMI ≥ 85th percentile to <95th percentile). In children 2-9 years of age with obesity (BMI ≥ 95th percentile), providers may choose to screen for dyslipidemia. [Hampl: 2023].

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes is increasing in the pediatric population, and overweight/obesity is a strong predictor. [Mayer-Davis: 2017] The AAP recommends screening for abnormal glucose metabolism in children 10 years and older with obesity (BMI ≥ 95th percentile) with fasting plasma glucose, oral glucose tolerance test, or glycosylated hemoglobin. In addition, screening is recommended in children 10 years and older with overweight (BMI ≥ 85th percentile to <95th percentile in the presence of additional risk factors (maternal history of diabetes/gestational diabetes, family history of diabetes in 1st or 2nd degree relative, signs of insulin resistance, and use of obesogenic medications. [Hampl: 2023] [Andes: 2020] See Pediatric Type 2 Diabetes Screening & Management Care Process Model.

Children with overweight and obesity have increased risk of NAFLD, and some studies have reported rates as high as 34% in children with obesity. [Anderson: 2015] The AAP and the North American Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) recommend screening for NAFLD using aspartate transaminase in children 10 years and older with obesity (BMI ≥ 95th percentile). Additionally, children 10 years and older with overweight (BMI ≥ 85th percentile to <95th percentile. [Hampl: 2023] should be screened in the presence of additional risk factors (family history of NAFLD, central adiposity, signs of insulin resistance, pre-diabetes, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and sleep apnea. [Hampl: 2023]

HTN in childhood increases the risk of HTN in adulthood, and its prevalence is directly related to BMI percentile. [Chen: 2008] The AAP recommends measuring blood pressure at every visit starting at 3 years in children and adolescents with overweight and obesity. [Hampl: 2023]

Risks of Screening

Consideration must be given to the risk of performing unnecessary testing and its accompanying cost. However, given the large impact of the morbidity associated with obesity-related conditions, it is likely that the benefits outweigh the risks. Furthermore, there seems to be a higher likelihood of severe disease or progression in pediatric patients with obesity compared to adult counterparts. [Harlow: 2018] [Newton: 2016] [Holterman: 2013] This highlights the importance of identifying and treating these conditions sooner rather than later.Treating and Preventing Obesity

Treatment

- Reducing sugar-sweetened beverages (see MyPlate (USDA)

- Encouraging 60 minutes of daily activity

- Reducing sedentary behavior – largely by decreasing screen time. [Daniels: 2015]

Prevention

Some additional strategies used for treatment can, in theory, be used for prevention. The following have moderately convincing evidence or expert consensus to support their role in prevention, and they likely have health benefits beyond obesity treatment and prevention. Many of these are shown to improve outcomes even without weight loss or reduction in BMI. [Lumeng: 2015] [Davis: 2007]

5-2-1-0 A DAY

The 5-2-1-0 message is widely disseminated

and supported by a number of groups and organizations. It is a simple

message that clinicians can deliver to parents and children:

- Five servings of fruits and vegetables

- Less than two hours of screen time

- More than one hour of exercise

- Zero sweetened beverages

Consistent with the AAP approval of a serving of 100% juice, some have modified this to “5-2-1-almost none per day.

Limit Screen Time

Most studies regarding screen time

have focused on television. Some, but not all, studies have shown a

correlation between hours of TV watched and risk of increased adiposity.

Given this correlation, the AAP recommends no screen time for children under

18 months and 1 hour or less per day for children aged 2-5 years. [Healthy: 2023] For children over age 5, the

AAP suggests families have a plan to limit excessive use but without an

official upper limit. [Council: 2022]

60 Minutes of Daily Exercise

Aerobic exercise is

associated with multiple benefits in pediatric patients, including improved

bone health, decreased BMI, cardiorespiratory fitness, improved cognition,

and reduced risk of depression. The United States Department of Health and

Human Services recommends 60 minutes daily or more of moderate to vigorous

aerobic exercise. [Piercy: 2018]

No (or almost no) Sweetened Beverages

Strong evidence

associates the intake of sweetened beverages with obesity or excess

adiposity. [Luger: 2017] Sweetened

beverages include soda, sports beverages, and sweetened fruit drinks.

Current evidence does not support an association between 100% fruit juice

and obesity unless consumed in “large quantities.” The AAP currently

recommends that consumption of 100% fruit juice be limited to 1 serving (4-6

oz.) per day for children between 1 and 6 years old and no more than 8 oz

for children ages 7-14 years old. [Korioth: 2019] Some pediatricians have questioned the benefits of juice

and have recommended that its consumption be even more limited—perhaps to

“none.”

Breakfast

Skipping breakfast has been associated with

more metabolic dysfunction, including greater waist circumference, higher

fasting insulin, higher total cholesterol, and higher LDL, even after

adjusting for other potential confounders. [Odegaard: 2013]

[Szajewska: 2010] Overweight and obese adolescents are more likely than

those of normal weight to skip breakfast. When they do eat breakfast, it is

smaller and of a lower nutritional quality. Although no evidence

demonstrates that eating breakfast will prevent obesity, no evidence

suggests that such a strategy would be harmful.

Appropriate Sleep

There is an association between higher

BMI and shorter sleep duration. It may be that decreased sleep increases the

hormone ghrelin and decreases leptin, which leads to hunger. Insufficient

sleep is associated with increased calorie consumption and decreased

physical activity due to fatigue. Encouraging healthy sleep patterns is

recommended. [Ruan: 2015]

Nutrition and Children with Complex Health Care Needs

Parents of CYSHCN are often concerned about whether their child’s nutritional needs are being met. Some of these children may have difficulty achieving adequate calories to support appropriate growth, and parents may offer foods that are higher in “empty” calories in the hope that their child will gain weight. Achieving the recommended 5 servings a day of fruits and vegetables may be particularly challenging. It is important to individualize recommendations for calories and dietary constituents based on the child’s condition and potential for physical activity. Careful monitoring of growth trajectories to ensure that the child’s growth is consistent and that weight gain is not excessive for the child’s height is probably the best way of knowing whether more specific recommendations regarding the child’s diet are necessary. It may be appropriate to refer the family to a registered dietician for specific advice regarding the child’s unique needs.

Services & Referrals

Behavioral Therapies

(see NW providers

[1])

Families with children <10 years old may benefit from a

behavioral program that offers child and family counseling focusing on learning

new skills, problem-solving, and managing feelings.

Food & Nutrition > …

(see NW providers

[3])

Refer at onset (or during the first appointment with a patient

with obesity) to receive counseling regarding diet and assist with diagnosing

eating disorders. Refer to assist in treating eating disorders and teaching

healthy living habits.

Weight Loss Programs

(see NW providers

[0])

Referral may be helpful to reach weight goals.

Resources

Information & Support

Related Portal Content:

For Professionals

Obesity & Children with Special Needs (AbilityPath.org) ( 1.7 MB)

1.7 MB)

Excellent presentation detailing the particular risks for CYSCHN and obesity. Includes practical approaches for parents and

health care professionals.

Disability and Obesity (CDC)

Summarizes the factors that contribute to some individuals with disabilities being at higher risk for obesity and provides

guidance on possible interventions; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For Parents and Patients

Live Well (Intermountain Healthcare)

Education for families about healthy lifestyles; Intermountain Healthcare.

MyPlate (USDA)

Offers personalized eating plans and interactive tools to help plan and assess food choices; US Department of Agriculture.

Let's Move! (obamawhitehousearchives.gov)

Resources for families, parents, children, communities, and health care providers for providing healthy food in schools, improving

access to healthy, affordable foods, and increasing physical activity; First Lady Michelle Obama’s initiative for healthy

families.

Nutrition & Fitness (KidsHealth)

Nutrition, fitness, and overall health information for parents, kids, teens, and educators. Includes recipes, safety tips,

and discussion of feelings; sponsored by the Nemours Foundation.

Tools

BMI Males 2-20 Years (CDC) ( 62 KB)

62 KB)

Body mass index for age percentiles; Centers for Disease Control.

BMI Females 2-20 Years (CDC) ( 68 KB)

68 KB)

Body mass index for age percentiles; Centers for Disease Control.

BMI Percentile Calculator for Children and Teens (CDC)

The calculator provides BMI, BMI-for-age percentile, and an easy-to-read interpretation. Results can also be viewed on a CDC

BMI-for-age growth chart; Centers for Disease Control & Prevention.

Clinical Growth Charts (CDC & WHO)

Provides links to 2 comprehensive sets of growth charts: the CDC Clinical Growth Charts (preferred for use with children 24

months and older) and the World Health Organization (WHO) Charts (preferred for children under 24 months); Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention.

Services for Patients & Families Nationwide (NW)

| Service Categories | # of providers* in: | NW | Partner states (4) (show) | | NM | NV | RI | UT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Therapies | 1 | 17 | 19 | 32 | 36 | ||||

| Dieticians and Nutritionists | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 6 | ||||

| Food & Nutrition | 3 | 8 | 286 | 31 | 210 | ||||

| Weight Loss Programs | 2 | ||||||||

For services not listed above, browse our Services categories or search our database.

* number of provider listings may vary by how states categorize services, whether providers are listed by organization or individual, how services are organized in the state, and other factors; Nationwide (NW) providers are generally limited to web-based services, provider locator services, and organizations that serve children from across the nation.

Helpful Articles

Nelson VR, Masocol RV, Asif IM.

Associations Between the Physical Activity Vital Sign and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in High-Risk Youth and Adolescents.

Sports Health.

2020;12(1):23-28.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Grossman DC, Bibbins-Domingo K, Curry SJ, Barry MJ, Davidson KW, Doubeni CA, Epling JW Jr, Kemper AR, Krist AH, Kurth AE,

Landefeld CS, Mangione CM, Phipps MG, Silverstein M, Simon MA, Tseng CW.

Screening for Obesity in Children and Adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement.

JAMA.

2017;317(23):2417-2426.

PubMed abstract

Bandini L, Danielson M, Esposito LE, Foley JT, Fox MH, Frey GC, Fleming RK, Krahn G, Must A, Porretta DL, Rodgers AB, Stanish

H, Urv T, Vogel LC, Humphries K.

Obesity in children with developmental and/or physical disabilities.

Disabil Health J.

2015;8(3):309-16.

PubMed abstract

Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Galuska DA, George SM, Olson RD.

The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans.

JAMA.

2018;320(19):2020-2028.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Council on Communication and Media.

Media and Young Minds.

Pediatrics.

2022;138(5):reaffirmed 9/26/2022.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Authors & Reviewers

| Authors: | Rachel Tanz, MD |

| Jose Morales Moreno, MD |

Page Bibliography

Anderson EL, Howe LD, Jones HE, Higgins JP, Lawlor DA, Fraser A.

The Prevalence of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.

PLoS One.

2015;10(10):e0140908.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Andes LJ, Cheng YJ, Rolka DB, Gregg EW, Imperatore G.

Prevalence of Prediabetes Among Adolescents and Young Adults in the United States, 2005-2016.

JAMA Pediatr.

2020;174(2):e194498.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Ayer J, Charakida M, Deanfield JE, Celermajer DS.

Lifetime risk: childhood obesity and cardiovascular risk.

Eur Heart J.

2015;36(22):1371-6.

PubMed abstract

Bandini L, Danielson M, Esposito LE, Foley JT, Fox MH, Frey GC, Fleming RK, Krahn G, Must A, Porretta DL, Rodgers AB, Stanish

H, Urv T, Vogel LC, Humphries K.

Obesity in children with developmental and/or physical disabilities.

Disabil Health J.

2015;8(3):309-16.

PubMed abstract

Bates CR, Buscemi J, Nicholson LM, Cory M, Jagpal A, Bohnert AM.

Links between the organization of the family home environment and child obesity: a systematic review.

Obes Rev.

2018;19(5):716-727.

PubMed abstract

Chen X, Wang Y.

Tracking of blood pressure from childhood to adulthood: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis.

Circulation.

2008;117(25):3171-80.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Council on Communication and Media.

Media and Young Minds.

Pediatrics.

2022;138(5):reaffirmed 9/26/2022.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Daniels SR, Hassink SG.

The Role of the Pediatrician in Primary Prevention of Obesity.

Pediatrics.

2015;136(1):e275-92.

PubMed abstract

Davis MM, Gance-Cleveland B, Hassink S, Johnson R, Paradis G, Resnicow K.

Recommendations for prevention of childhood obesity.

Pediatrics.

2007;120 Suppl 4:S229-53.

PubMed abstract

From a special supplement to Pediatrics; it has numerous references and provides a rigorous review of current evidence. It

also addresses the complex issue of influencing behavior through the use of Motivational Interviewing and the Chronic Care

Model.

Divers J, Mayer-Davis EJ, Lawrence JM, Isom S, Dabelea D, Dolan L, Imperatore G, Marcovina S, Pettitt DJ, Pihoker C, Hamman

RF, Saydah S, Wagenknecht LE.

Trends in Incidence of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Among Youths - Selected Counties and Indian Reservations, United States,

2002-2015.

MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.

2020;69(6):161-165.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Elks CE, den Hoed M, Zhao JH, Sharp SJ, Wareham NJ, Loos RJ, Ong KK.

Variability in the heritability of body mass index: a systematic review and meta-regression.

Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

2012;3:29.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Grossman DC, Bibbins-Domingo K, Curry SJ, Barry MJ, Davidson KW, Doubeni CA, Epling JW Jr, Kemper AR, Krist AH, Kurth AE,

Landefeld CS, Mangione CM, Phipps MG, Silverstein M, Simon MA, Tseng CW.

Screening for Obesity in Children and Adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement.

JAMA.

2017;317(23):2417-2426.

PubMed abstract

Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL.

Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States, 2015-2016.

NCHS Data Brief.

2017(288):1-8.

PubMed abstract

Hampl SE, Hassink SG, Skinner AC, Armstrong SC, Barlow SE, Bolling CF, Avila Edwards KC, Eneli I, Hamre R, Joseph MM, Lunsford

D, Mendonca E, Michalsky MP, Mirza N, Ochoa ER, Sharifi M, Staiano AE, Weedn AE, Flinn SK, Lindros J, Okechukwu K.

Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Obesity.

Pediatrics.

2023;151(2).

PubMed abstract / Full Text

This is the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)’s first clinical practice guideline (CPG) outlining evidence-based evaluation

and treatment of children and adolescents with overweight and obesity.

Hampl SE, Hassink SG, Skinner AC, Armstrong SC, Barlow SE, Bolling CF, Avila Edwards KC, Eneli I, Hamre R, Joseph MM, Lunsford

D, Mendonca E, Michalsky MP, Mirza N, Ochoa ER, Sharifi M, Staiano AE, Weedn AE, Flinn SK, Lindros J, Okechukwu K.

Executive Summary: Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Obesity.

Pediatrics.

2023;151(2).

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Hampl SE, Hassink SG, Skinner AC, Armstrong SC, Barlow SE, Bolling CF, Avila Edwards KC, Eneli I, Hamre R, Joseph MM, Lunsford

D, Mendonca E, Michalsky MP, Mirza N, Ochoa ER, Sharifi M, Staiano AE, Weedn AE, Flinn SK, Lindros J, Okechukwu K.

Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Obesity.

Pediatrics.

2023;151(2).

PubMed abstract / Full Text

This is the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)’s first clinical practice guideline (CPG) outlining evidence-based evaluation

and treatment of children and adolescents with overweight and obesity.

Harlow KE, Africa JA, Wells A, Belt PH, Behling CA, Jain AK, Molleston JP, Newton KP, Rosenthal P, Vos MB, Xanthakos SA, Lavine

JE, Schwimmer JB.

Clinically Actionable Hypercholesterolemia and Hypertriglyceridemia in Children with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease.

J Pediatr.

2018;198:76-83.e2.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Healthy Children.

Where We Stand: Screen Time.

American Academy of Pediatrics; (2023)

https://www.healthychildren.org/English/family-life/Media/Pages/Where-.... Accessed on 01/26/2024.

Holterman AX, Guzman G, Fantuzzi G, Wang H, Aigner K, Browne A, Holterman M.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in severely obese adolescent and adult patients.

Obesity (Silver Spring).

2013;21(3):591-7.

PubMed abstract

Juonala M, Magnussen CG, Berenson GS, Venn A, Burns TL, Sabin MA, Srinivasan SR, Daniels SR, Davis PH, Chen W, Sun C, Cheung

M, Viikari JS, Dwyer T, Raitakari OT.

Childhood adiposity, adult adiposity, and cardiovascular risk factors.

N Engl J Med.

2011;365(20):1876-85.

PubMed abstract

Korioth T.

Added sugar in kids’ diets: How much is too much?.

AAP News. 2019; https://publications.aap.org/aapnews/news/7331/Added-sugar-in-kids-die...

Larqué E, Labayen I, Flodmark CE, Lissau I, Czernin S, Moreno LA, Pietrobelli A, Widhalm K.

From conception to infancy - early risk factors for childhood obesity.

Nat Rev Endocrinol.

2019;15(8):456-478.

PubMed abstract

Logan KM, Gale C, Hyde MJ, Santhakumaran S, Modi N.

Diabetes in pregnancy and infant adiposity: systematic review and meta-analysis.

Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed.

2017;102(1):F65-F72.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Luger M, Lafontan M, Bes-Rastrollo M, Winzer E, Yumuk V, Farpour-Lambert N.

Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Weight Gain in Children and Adults: A Systematic Review from 2013 to 2015 and a Comparison with

Previous Studies.

Obes Facts.

2017;10(6):674-693.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Lumeng JC, Taveras EM, Birch L, Yanovski SZ.

Prevention of obesity in infancy and early childhood: a National Institutes of Health workshop.

JAMA Pediatr.

2015;169(5):484-90.

PubMed abstract

Malozowski S.

Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adolescents with Obesity.

N Engl J Med.

2023;388(12):1145-1146.

PubMed abstract

Mayer-Davis EJ, Lawrence JM, Dabelea D, Divers J, Isom S, Dolan L, Imperatore G, Linder B, Marcovina S, Pettitt DJ, Pihoker

C, Saydah S, Wagenknecht L.

Incidence Trends of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes among Youths, 2002-2012.

N Engl J Med.

2017;376(15):1419-1429.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Minihan PM, Must A, Anderson B, Popper B, Dworetzky B.

Children with special health care needs: acknowledging the dilemma of difference in policy responses to obesity.

Prev Chronic Dis.

2011;8(5):A95.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Morgan AR, Thompson JM, Murphy R, Black PN, Lam WJ, Ferguson LR, Mitchell EA.

Obesity and diabetes genes are associated with being born small for gestational age: results from the Auckland Birthweight

Collaborative study.

BMC Med Genet.

2010;11:125.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Nelson VR, Masocol RV, Asif IM.

Associations Between the Physical Activity Vital Sign and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in High-Risk Youth and Adolescents.

Sports Health.

2020;12(1):23-28.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Newton KP, Hou J, Crimmins NA, Lavine JE, Barlow SE, Xanthakos SA, Africa J, Behling C, Donithan M, Clark JM, Schwimmer JB.

Prevalence of Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes in Children With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease.

JAMA Pediatr.

2016;170(10):e161971.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Nguyen D, Kit B, Carroll M.

Abnormal Cholesterol Among Children and Adolescents in the United States, 2011-2014.

NCHS Data Brief.

2015(228):1-8.

PubMed abstract

Odegaard AO, Jacobs DR Jr, Steffen LM, Van Horn L, Ludwig DS, Pereira MA.

Breakfast frequency and development of metabolic risk.

Diabetes Care.

2013;36(10):3100-6.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Galuska DA, George SM, Olson RD.

The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans.

JAMA.

2018;320(19):2020-2028.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Qureshi R, Jadotte Y, Zha P, Porter SA, Holly C, Salmond S, Watkins EA.

The association between prenatal exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and childhood obesity: a systematic review.

JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep.

2018;16(8):1643-1662.

PubMed abstract

Rajjo T, Almasri J, Al Nofal A, Farah W, Alsawas M, Ahmed AT, Mohammed K, Kanwar A, Asi N, Wang Z, Prokop LJ, Murad MH.

The Association of Weight Loss and Cardiometabolic Outcomes in Obese Children: Systematic Review and Meta-regression.

J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

2017;102(3):758-762.

PubMed abstract

Ruan H, Xun P, Cai W, He K, Tang Q.

Habitual Sleep Duration and Risk of Childhood Obesity: Systematic Review and Dose-response Meta-analysis of Prospective Cohort

Studies.

Sci Rep.

2015;5:16160.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Simmonds M, Llewellyn A, Owen CG, Woolacott N.

Simple tests for the diagnosis of childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Obes Rev.

2016.

PubMed abstract

Skinner AC, Perrin EM, Moss LA, Skelton JA.

Cardiometabolic Risks and Severity of Obesity in Children and Young Adults.

N Engl J Med.

2015;373(14):1307-17.

PubMed abstract

Sokol RL, Qin B, Poti JM.

Parenting styles and body mass index: a systematic review of prospective studies among children.

Obes Rev.

2017;18(3):281-292.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Szajewska H, Ruszczynski M.

Systematic review demonstrating that breakfast consumption influences body weight outcomes in children and adolescents in

Europe.

Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr.

2010;50(2):113-9.

PubMed abstract

Vanina Y, Podolskaya A, Sedky K, Shahab H, Siddiqui A, Munshi F, Lippmann S.

Body weight changes associated with psychopharmacology.

Psychiatr Serv.

2002;53(7):842-7.

PubMed abstract

Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH.

Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity.

N Engl J Med.

1997;337(13):869-73.

PubMed abstract

Zheng M, Lamb KE, Grimes C, Laws R, Bolton K, Ong KK, Campbell K.

Rapid weight gain during infancy and subsequent adiposity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of evidence.

Obes Rev.

2018;19(3):321-332.

PubMed abstract / Full Text